The imperfect recollections of a grateful middle child who always knew that she was loved

My mother was a photographer. Those who knew her would recall the constant presence of a camera around her neck when she was travelling. I was so used to it I stopped being embarrassed, but I didn't really appreciate its power until we moved away from home. It was mum’s constant streams of photographs that kept me informed and connected to her world long before the days of FaceTime and Zoom.

The earliest memory I have of my mother that I think is truly my memory, not something from a photograph or “remembered” after a discussion with my older sister, is of her patiently waiting, sitting on the edge of my bed as I insisted she stay there so I could get back to sleep. “Roll over and go back to sleep” she would say, and I have a clear image of her, silhouetted in the doorway, sitting on the edge of my bed and there was great comfort in knowing she would remain there until I fell asleep, as inevitably I did.

I still roll over to go back to sleep.

My mum drove me to school in the Land Rover on my first day of Grade 1. This wasn't something she usually did, we all simply walked to school and back each day. But for some reason, this day she drove me, this first day. But she was running late, she'd been caught up in the surgery and I was anxious, so she drove me. We raced up to the parade ground where everybody was standing, later than we should have been and I can still see it in my mind's eye. I clung, was it to her hand or to her skirt, I can’t remember, and I didn't want her to go. I wanted to go home with her. I didn't want to stay at school even though my brother and my sister were there and would, and did, look after me.

I wanted to go home with mum.

My mother was sporty. Oh my gosh, you should've seen her! I think she was 5-foot 1 inch (156 cm) when young and the last time she let me see how tall she was, she was 4-foot 11 ½ inches (151 cm) and shrinking fast. She was a water skier and a snow skier, she learned to rollerblade in her 50s and to windsurf, being much better at both of those than I ever was. My mother was a fast walker. It was nothing I ever considered, but when I met my husband's family, they commented on how fast I walked, reasoning it was because I myself was tall (175 cm) therefore could take long strides. It took me a little while to realise it, but I was not a fast walker because I was tall, I was a fast walker because that's how fast I had to walk to keep up with mum. My stride is indeed much longer than my mother’s was, but mum sure could walk fast!

My mother was a sewer and the sewing cupboard sat on one side of the hallway with the Pfaff machine, paper patterns, bobbins and threads and scissors. Never use the sewing scissors for cutting paper - that was a one-way ticket to trouble! There were leftover bits of fabric and buttons, always buttons. When we were little, she sewed a number of our clothes, as we grew older, she paid Mrs Burrell to do so. She would still do simple stuff though, it annoyed her no end to pay someone to do something simple. For our 17th birthdays both my sister and I received a sewing machine and here I am, 40 years later, I still have that machine and I've used it in the last week.

My mum was clever, really, really clever. At a time where to go on to a public high school you had to pass an exam, my mum topped the state, outperforming all other students, male and female. Mum had a choice of scholarships. She could attend Brisbane Girls Grammar or St Margaret's and she chose Girls Grammar because she preferred the blue and white of the Grammar uniform over the blue and brown of St Margaret’s! When asked by the formidable Miss Lilley what she wanted to be after school, my mum volunteered “PE teacher” to which Miss Lilley sternly rebuked her “Grammar girls do not become teachers!” My mum's name is on the honour board at Brisbane Girls Grammar three times. She won a scholarship to the University of Queensland to study medicine, one of only five girls in her year. When the lectures about obstetrics were being given, mum and her female companions had to wait outside, for such discussions were not for the fairer sex.

My mother was a doctor, but she was called Mrs Luck not Dr Luck. My father was also a doctor and he was referred to as Dr Luck - in the 1960s, you never called the doctor by their first name, so it couldn't be Dr Roy and Dr Marce, it had to be Dr Luck and Mrs Luck. I don't know if this bothered her, it wasn't anything we ever discussed, but I do know towards the end of her life when she was not well enough to renew her medical licence, that this angered her greatly. She railed against me, accusing me of taking away her identity. She told me how important it was to her to be a doctor and asked how would I feel when my time came and someone told me I was no longer a doctor? I tried to reason with her that she was still a doctor, that not being registered didn't take away her years of training and knowledge and experience, but that she was no longer well enough to write scripts or referrals and it was time to let the registration go.

It was a source of great sorrow.

Being a doctor was a very important part of my mother's identity.

My mother played the organ, this little one to start with and then dad bought her a double decker organ with pedals that were so far from her it was amazing that she could even reach them. She relaxed by playing, and if ever she was waiting for something to happen, she knew as soon as she sat down to play the organ, the phone would ring, the surgery doorbell would ding or the knock on the door would announce that the visitor had finally arrived. Oh, the inevitability of it all. She had our organ teacher play the organ at dad's memorial service and then gave the small one to her, which just seemed right.

My mother was a sneezer. Oh.my.goodness, she was a sneezer! If something got up her nose, she would sneeze and sneeze. Ah choo! Ah choo! Ah choo, ah choo, ah choo, ah choo, ah choo, ah choo, ah choo, ah choo, ah choo, ah choo, ah choo!!! I know it annoyed her, it annoyed ALL of us. Not that there was anything any of us could do about it, but it was so loud and so annoying! If she started to sneeze, you’d brace yourself because, sure as eggs, it was coming! She would hold her nose and make a funny little noise “ah ch”, but it would still repeat! I have the same habit, especially if consulting, but I’ve realised over the years, sometimes you just have to let the Ah Choo!! rip and get whatever it is that is in there out!

My mother was a reader. She loved learning, she loved reading and we had so many great discussions about Harry Potter. But the sickness that took her life damaged her memory and when the final book in the series came out, she no longer recalled the threads of the story and it was all simply confusing for her. We lost a last opportunity to talk about the intricacies of that storyline which still saddens me.

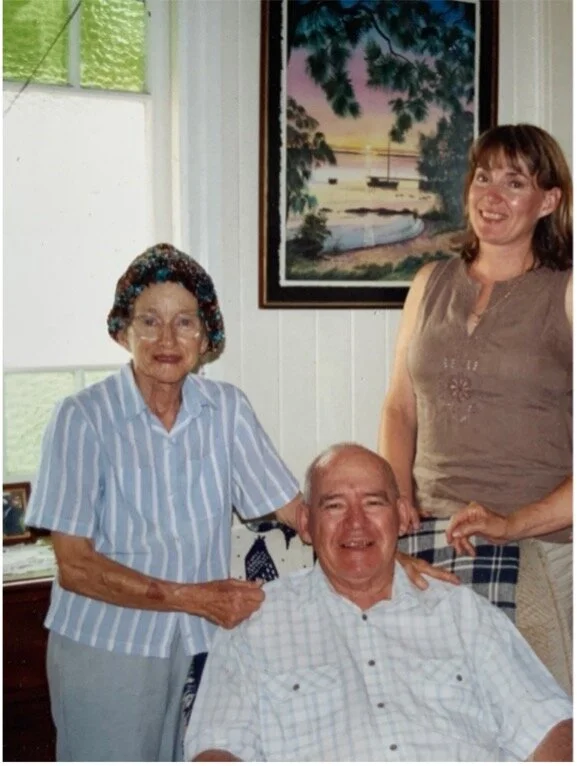

Vic must have taken this shot, mum was usually the one behind the camera, meaning we don’t have many with her in the frame.

My mother was a rural generalist before such a thing officially existed. She gave the anaesthetics, my dad did the operations and between them, they delivered most of my school friends. She had wanted to train in paediatrics but instead mum and dad left the hospital system when he failed to get a surgical training position and moved into country general practice. They worked to the top of their licence for decades, providing comprehensive whole of life care and inpatient care to our community. It was mum who delivered the twins in the back of the ambulance, when the ambulance realised they weren't going to make it to Nambour in time and pulled over in Cooroy, hoping one of the docs there would be able to help. It was mum who ordered the tests that diagnosed leukaemia in the university student who’d been told by the city GPs that she should stop partying so much. It was mum who recognised the rash on the young child and carried him across the backyard and over the road to the hospital, putting in the IV drip with the antibiotic that saved that child's life from the meningococcal meningitis she had recognised. One of the great joys of her life was attending that child's wedding.

My mum had an amazing speculum collection. As the only female GP within a very broad distance on the Sunshine Coast of Queensland, she attracted a lot of female patients for that regular check. She had different types and so many different sizes, all of which came to me when she retired. To this day, I have a couple of patients who know to ask for my mum's small speculum when I'm doing their pap smear, as this is the only one that is comfortable.

Mum was medical old school, as was dad. Look, feel, move. More mistakes are made by not looking then not knowing. Life before limb before function. It drove her crazy the way the modern practitioners would take a snippet of history and rush immediately into investigation, medication or referral. Medicine was something that took time and there were no shortcuts in her world. Which is why I often saw her breaking for lunch when I got home from school at 3:30 pm.

My mum was not a cook. She would joke that she could burn water and that her greatest kitchen tool was the can opener. But she didn't need to, the work they did allowed them to employ a housekeeper and Bev did the cooking: spaghetti bolognese, roast chicken, you name it, Bev cooked it for us. Mum was good with simple things like sausages and eggs and steak, although don't give her a thick piece of steak, that always came out wrong. She was good with mashed potato too, but nothing fancy. It just wasn't her skill.

My mother was a connector and a communicator. She kept in contact with her mother's extended family and people that I didn't even know I could possibly be related to. All their stories and how they were related to us. Old school friends, university and hospital colleagues – her recollection was encyclopaedic. She sent postcards and wrote letters, often including the photographs of whichever gathering had just passed. She made phone calls, she dropped in to visit. I think we had been in Sydney for all of a month when it really, really hit me how much I missed her. I don't think that a month had gone past in many, many years when mum hadn't dropped in to say hello on her way from the Sunshine Coast to the city to do this or that

My mum was not a fashion plate. She had a wig and a few very long frocks for special occasions that she would bring out in the 70s, but clothing was never something she was particularly bothered about and footwear was comfortable and practical. Nothing fancy, no stilettos for my mum. She did always wear stockings though, for work. That was simply something that you did. It took me decades to realise it was not something my generation had to do.

My mum was energetic. She would get up early and go to bed late. She never seemed to stop. She walked so fast, I always thought she could have competed for Australia in the Olympics! She had a bicycle that she would ride or rollerblades to go down the street. It disappointed her no end that she couldn't get anyone to go back to Perisher with her the year she had the over 70s annual ski pass.

My mum was a navigator for many years, helping my dad plan his flights but before she was a navigator, she wanted to be a pilot. My dad loved flying and got first a gliding licence then a fixed wing licence then a helicopter licence. This annoyed my mother no end, as her father had promised her should she get a University scholarship, he would pay for her to learn to fly. Unfortunately, he simply didn't have the funds, but all of her life she had wanted to fly. So when, in our teenage years, she would complain loudly that she had wanted to fly for longer than my father had and now he had the licence and she didn't, we would reply as teenagers are wont to do “What are you doing about it?” inviting her to solve her own problem. Which she did. At the age of 50 my mum got her pilots licence and she and dad spent many years flying around in a small fixed wing plane. Mum became friends with Nancy Bird Walton and a number of other magnificent women in the Australian Women Pilots’ Association. She once accompanied Nancy in a helicopter ride with Dick Smith.

My mum had an adventurous life.

My mum had a temper. Oh my goodness, she had such a temper! When she was in full flight, there was really nothing you could do except stand there and let it pass. And pass it did. She was quick to blow up but then it would blow over. Dad on the other hand had a slow burn temper. His would simmer for weeks or months or years and when he finally blew, he would remind you of things that you said or did so long ago it was forgotten, except by him. I preferred my mother's temper; fast and furious but then forgotten.

It is the temper I inherited, or did I simply learn by observation?

My mother and I had all sorts of conversations that perhaps only mother and daughter who are doctor and doctor could do. We talked about things that you are not allowed to talk about, like how we never wanted to be unable to live life on our own terms, to be dependent on others for all our care. How we promised each other that, if that time ever came, we would put a pillow over the head and extinguish life. I don't know that either of us really meant it and neither of us ever attempted it, but we had a mutual understanding that there were things for us that were worse than death.

My mum was amazing. My mum was an incredible role model. My mum loved me, encouraged me, supported me and loved my husband and our sons.

My mum was vulnerable. 2006 was a dreadful year. Dad was diagnosed with an occipital glioblastoma in May and mum developed an aggressive non-Hodgkin’s B cell Lymphoma in September. The steroids that made her high, bordering on manic, weakened and wasted her away and the neutropenic fever damaged her brain and changed her personality in ways I still regret.

I was there that week. We had gone to stay with them so I could watch mum and if necessary, wield the antipsychotics when she went way too high on the steroids that were needed before her next round of chemo. I was there and I saw the heat shimmering off her and I realised with great sadness that my father no longer had his clinical skills. He had not recognised how sick she was. It was I who took her to the Noosa Hospital where they enacted the protocol for fever in a patient on chemotherapy. It was I who knew how close she came to dying and I who was so glad I was there to stop it.

And it was I who wondered in the weeks, months and years to come, why I hadn't simply let her go. She became cruel and mean, angry and bitter towards my dad. She had the right to be aggrieved but that time was long past, and he was dying, indeed, would be dead within the month.

When the agitated depression that she sunk into after dad's death became too much for any of us to manage, she was admitted to a private psych hospital. That is where I visited to give her the last Harry Potter book, but although she tried, she was unable to remember the threads of that intricate story. It was there that I took the lanyard with her senior’s ski pass and put it, along with her photographs of the family, on the walls, so she would know we were with her. And it was there that I left her standing in the doorway to her room, as I walked away down the long corridor to the exit. I can still see her in her white nightie, so small, so fragile. I didn't have a daughter, but it felt like I was abandoning one. I wonder to myself how she felt in that moment, and if it was the same emotion washing over her as came over me on that first day at school – did she just want to hold onto my hand/my skirt and come home with me? As I sat in the car, a wave of anguish washed over me and I had to fight incredibly hard to hold back the gulps of grief, concentrating on shielding my sons from the impact of leaving mum behind.

I wanted to tell her that it would be alright, but it wasn’t, and it never would be again.

I hated what the cancer and the chemotherapy did to her. I hated watching her strong, sporty body become so weak she could barely stand up from a crouch. I hated what it did to her mind. I hated how she couldn't get out of the house because she couldn't decide what to wear or find the right pair of shoes - they were all comfortable, they all fit, she had lots of different colours. I hated what it did to her as I wondered what the point was, why she was still with us? Months and months turned into years of grief, anger, anguish, arguing with myself and arguing with God, before I finally came to appreciate the final lesson that my mum taught me.

In walking through the journey with her, I learned that I could love someone, even when there was nothing in it for me.

Even when it cost me dearly, I still loved her.

This is and has had to be enough.

I remember hearing the news about her cancer metastasising - I was driving across the Story Bridge in Brisbane when her GP, who was at medical school with me, broke the news. Unfortunately for mum's GP, she was literally about to fly out of Brisbane and did not have the time to do justice to the breaking of such news and as much as she didn't want to ask, she asked, and as much as I didn't want to accept, I accepted the challenge of telling mum.

I did not want to be the one to break the news to my mother that her increasing pain was due to metastatic cancer and yet I didn't want anybody else to do it either. So I sat in the living room with my siblings, holding mums’ hand and I told her that we had lost the battle to fight the cancer and it was time to up the battle to control the pain.

But mum didn't want to stop. Despite all of our previous conversations, she was not ready to let go, she didn’t want to die. But that choice was gone – there was nothing more left to offer except kindness and palliation in the hope of a good death.

Ron and I got mum back to the Lake for one last visit. Not that Cathy wanted us to take her, recognising how fragile she was and not being sure that we would look after her properly. Mum didn’t have the strength to walk the route she’d walked thousands and thousands of times over the previous 46 years, so we pushed her in a wheelchair. So many last goodbyes.

She drew her last breath less than two weeks later.

The final gift my mother gave me was the privilege of being in the room when she died. I was spending the week at my sister’s, where mum was receiving palliative care and as the end drew near, I went to administer the prescribed morphine for her pain, only too aware that pressure areas were developing and the ominous yet welcome change in her breathing, her noisy, rattly breathing. For some reason I couldn't get the needle into the line and knowing I was doing something wrong, I called my sister, who came and showed me. As I went to administer the morphine, I heard the breathing stop.

That noisy, rattly breathing stopped.

Silence fell.

And I turned my head just in time to see the colour drain from her face.

In a quiet, soft voice I said “Cath, she's gone.”

My sister cried out loud and I stood behind her as she gave mum her final kiss goodbye.

And my world was forever slower, darker, colder, smaller.

The night mum died was busy. Vic came, Vanessa and Bruce were there, the folk from the funeral directors came, but it’s a bit blurry. Mary, her GP, came and certified her deceased. It was late when we settled down to sleep and I was on the floor in the living room well past midnight, restless, trying to sleep, but still aware when I heard Cathy get up to go to the loo. And then it happened. She sneezed. Ah choo, ah choo, ah choo, ah choo, ah choo, ah choo, ah choo! For some reason, I counted them and there were seven sneezes. Loud sneezes. Mum-loud sneezes. Cathy was not a sneezer; mum was a sneezer.

I mentioned the sneezes to Cathy the next morning. She looked at me knowingly and there was an understanding that passed between the two of us as she said in a very matter-of-fact way, “It was mum, letting me know she is ok”. Nothing more needed to be said.

Mum, I know that you were proud of me and I know that you loved me. I know that I miss you and will always miss you. Thank you for being such an amazing role model and such a big part of my life. Mum, you set the pace and I've not only kept the pace, I’ve gone on to do all sorts of everything that you would never have imagined but you would be so pleased to see. I feel your presence, quietly watching over me. And I can still see you sitting there, silhouetted against the doorway, forever young, forever strong and sporty and energetic.

So, thank you mum

yours are the shoulders on which I have always stood

and I will miss you until my dying breath

Dr Wendy Burton

February 9, 2021

Dr Marceline Dorothy Victoria Luck 24/5/31 – 5/7/2009 MBBS (Qld)

Dr Victor Roy Luck 15/8/33 – 26/2/2007 MBBS (Qld)

Dr Gwendoline (Wendy) Ruth Burton (nee Luck) MBBS (Qld) FRACGP (Hon)